Against all good sense, I'm allowed back on TechTalk radio to reveal how Einstein originally composed his mass-energy equivalence equation in 1905, because it didn't look anything like E=mc2.

The rest of the show is dedicated to snarky but cogent discussion of deception and identity on Facebook, which is a much better use of your time. Before I leave, I toss a "Google vs. Sci-Fi" grenade over my shoulder. Give a listen; just fast-forward when you hear my voice.

As always, my complete litany of podcast transgressions is available here.

The personal blog of Jay Garmon: professional geek, Web entrepreneur, and occasional science fiction writer.

Showing posts with label Albert Einstein. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Albert Einstein. Show all posts

Wednesday, October 02, 2013

Monday, September 27, 2010

According to Einstein's famous equation, how many food calories are there in a single gram of mass?

Image via WikipediaExactly 105 years ago today -- Sept. 27, 1905 -- Albert Einstein published his paper "Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?" in Annalen der Physik, introducing the world to his famous equation, E = mc2. Except E = mc2 didn't actually appear in Einstein's original paper; Uncle Albert described his formula in prose, using different variables to express both energy and the speed of light. Translating from the original German, Einstein wrote:

Image via WikipediaExactly 105 years ago today -- Sept. 27, 1905 -- Albert Einstein published his paper "Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?" in Annalen der Physik, introducing the world to his famous equation, E = mc2. Except E = mc2 didn't actually appear in Einstein's original paper; Uncle Albert described his formula in prose, using different variables to express both energy and the speed of light. Translating from the original German, Einstein wrote:If a body gives off the energy L in the form of radiation, its mass diminishes by L/V2.The V in this case is the 1920s-era standard variable for the speed of light (which Einstein argued was constant). Thus, if you wrote out the mass-energy equivalence equation as Einstein originally described it, you'd get m = L/V2.

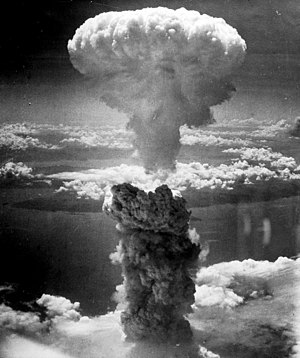

The upshot of Einstein's mass-energy equivalence and the relativity it helps describe is that all matter can be converted into a predictable amount of energy -- a large predictable amount of energy. Fortunately, only in very rare circumstances can matter be efficiently and explicitly converted entirely into its equivalent energy. We don't unleash all of our food energy when we digest it, for example, because we're unlocking its chemical energy, not its nuclear energy. That's a very good thing, as E = mc2 would make your average slice of cheesecake exponentially more fattening (and destructive).

According to Einstein's famous equation, how many food calories are there in a single gram of mass?

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

What highly explosive technology was originally patented on July 4?

As the Simpsons video above teaches us, there's no better way to celebrate the independence of our nation than by blowing up a small part of it. Indeed, setting off fireworks on Independence Day has been an American tradition since the holiday's first observance on July 4, 1777. Still, July 4th is a date with a long association with explosive events -- even those separate from American residents telling off British monarchs via the indulgent ignition of gunpowder.

In fact, on one particular July 4, perhaps the most historically significant explosive technology ever created was patented -- and no American was involved.

What highly explosive technology was originally patented on July 4?

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Truly Trivial: What famous physics phenomenon did Einstein refuse to believe was possible?

Image via Wikipedia

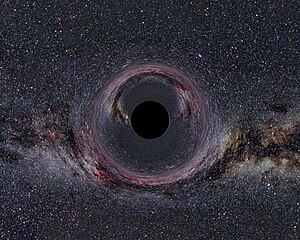

Image via WikipediaIndeed, Einstein's work on relativity put him at odds with some of the most imminent minds in the history of physics, including Neils Bohr (with whom Einstein waged a series of friendly if highly contest debates on quantum mechanics) and Karl Heisenberg. Often, Einstein proved his critics wrong, rewriting central theses of physics as he went. Still, Einstein was not infallible, and he not infrequently was proven wrong.

Ironically, one of Einstein's most famous missteps was a lifelong refusal to accept the possibility of a certain famous astrophysical phenomenon. Even more ironic, this theoretical basis of this phenomenon is based almost entirely on Einstein's own principles of relativity.

What famous astrophysical phenomenon -- proven possible by relativity -- did Einstein spent his career arguing against?

Thursday, July 09, 2009

Nerd Word of the Week: RKV

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Newton's second law holds that force equals mass multiplied by rate of acceleration. Thus, even a small mass moving at sufficient acceleration can generate significant force. "Conventional" kinetic weapons apply this law by simply dropping large, inert masses from planetary orbit (like the tungsten rods dropped from satellites in Warren Ellis's Global Frequency), allowing gravity to accelerate the payload to destructive velocity. RKVs go one step further, using vast interstellar distances to accelerate kinetic warheads to near-light speed, multiplying the force of their impact to catastrophic -- even planet-killing -- extremes.

RKVs are often a favorite plot device for hard sci-fi authors, including Larry Niven in his Known Space series, Charles Stross in Iron Sunrise, Joe Haldeman in The Forever War, and Vernor Vinge in A Fire Upon the Deep. RKVs don't require that civilizations develop faster-than-light travel or communication, as even subluminal propulsion systems can accelerate weapons to relativistic speeds given enough time and distance. Thus, wars fought between planets and stars are an ideal theater of conflict for RKVs, especially if you don't have FTL sensors to see them coming.

I bring it up because: Today is the 54th anniversary of Russell-Einstein Manifesto. On July 9, 1955, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and nine other noted intellectuals signed an essay highlighting the unconscionable dangers posed by nuclear weapons and implored world leaders to seek other, non-atomic-armageddon means of guaranteeing security and resolving conflict. Many view the manifesto as Einstein's repudiation of the application of his scientific breakthroughs to martial purposes. Unfortunately for Uncle Al, science has always led the way to new and more efficient weapons. Even setting aside the fission/fusion applications of Einstein's theories, his work on relativity can be applied for mass destruction in numerous ways, including the often overlooked brute-force example of RKVs. Food for thought, and some great science fiction.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f8a27ab5-5337-4dc3-aee0-6c8cebeed036)