One of my New Year's resolutions was to note here at my blog when I appear on TechTalk Radio. I call in most Saturdays, so I got out of the habit of reposting the shows here (and Mike, the show's host, got out of the habit of posting the podcasts so I could link to them). We're (both) going to do better in 2015.

So here's our first swipe of 2015: TechTalk Ep 371 – Prognostications and Prevarications for 2015!

My contributions include predictions about how cyberwars will escalate to open combat this year, and a quiz about the intersection of US Congressmen and the NASA astronaut corps. It's more nerdy than it sounds. Give a listen.

And if this short stint doesn't satisfy you, my (admittedly incomplete) history of podcast appearances is available here.

The personal blog of Jay Garmon: professional geek, Web entrepreneur, and occasional science fiction writer.

Showing posts with label NASA. Show all posts

Showing posts with label NASA. Show all posts

Friday, January 09, 2015

Friday, September 06, 2013

I am returned to Techtalk Radio, discuss the end of the Space Shuttle program

After weeks of missed connections and conflicts, I'm finally back to dragging down the quality of TechTalk Radio. This week, I throw out a quick missive on smartwatches, some trivia on the last cargo item the Space Shuttle placed into orbit, and lay down a challenge about the secret history of Steve Ballmer.

More importantly, Mike and Dave go deep on Google Maps tech with Daniel Seiberg. You can fast-forward past my drivel to the good stuff, no worries.

Listen to the TechTalk podcast here.

More importantly, Mike and Dave go deep on Google Maps tech with Daniel Seiberg. You can fast-forward past my drivel to the good stuff, no worries.

Listen to the TechTalk podcast here.

Tuesday, November 08, 2011

Techtalk Trivia: What was the only manned space flight mission to take off on Halloween day?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

My latest TechTalk podcast/radio appearance was suitably seasonal: Ep. 248 – Every Day is Halloween!

TOPIC: Mike and Dave get together right before Halloween this year to tell you spooky tech stories … well, maybe not so spooky, but Dave does apologize for his comments about Steve Jobs from a few weeks ago, and an apology from the TechTalk show can seem almost supernatural in it’s rarity. Tablets and a possibly too-long discussion of IVR rounds out the show before …

Jay “Encyclopedia Garmonica” treats us to a totally a propos Halloweeny geek trivia question:

What was the only manned space flight mission to take off on Halloween day?And that leaves us ample time for some great seasonal coolsites of the week!

- PumpkinPatchesAndMore – Find all the local pumpkin patches in your area! Plus carving templates, recipes, and more.

- HalloweenPrintables – From the great folks at FreePrintables.net, come some cards, puzzles, and coloring pages just in time for Halloween!

- FantasyPumpkins – These are cool to look at all year, and include templates for many of the coolest pumpkins you’ve ever seen!

Wednesday, October 05, 2011

What were the 'controversial' call signs for the Apollo 10 spacecraft - The ones that got astronauts' naming rights taken away?

Image via WikipediaLittle known fact: Apollo 10 was the last NASA mission in which astronauts were allowed to assign call signs to their spacecraft. Since then, NASA public relations has had final say on naming rights, in no small part because the Apollo 10 crew chose "controversial" names for their command module and lunar lander.

Image via WikipediaLittle known fact: Apollo 10 was the last NASA mission in which astronauts were allowed to assign call signs to their spacecraft. Since then, NASA public relations has had final say on naming rights, in no small part because the Apollo 10 crew chose "controversial" names for their command module and lunar lander.So, what were those rights-robbing call signs? There are two places to find out:

- Techtalk Podcast #237: Apollo 10 astronauts gave what unconventional call signs to their lunar and command modules, marking the last time astronauts were allowed to provide the names?

- Geek Trivia: What were the 'controversial' call signs for the Apollo 10 spacecraft?

Old-school comics fans will get a kick out of this one. Promise.

Friday, July 08, 2011

I love manned spaceflight and I'm glad the space shuttle is dead

The space shuttle is the last vestige of NASA's poltical theater era, when big, showy, hideously inefficient and unsupportable technical projects were its bread and butter. It's Nixon-era tech -- literally -- strung along for all the same government inertia keep-the-contractors-happy idiocy that's bankrupting our national treasury.

Consider, the shuttle is a reusable spacecraft that isn't actually reusable, given that the SRBs and main fuel tank are either lost or nearly 100% refitted after every launch. It's a construction platform for a spacestation that only needs a construction platform to assemble because it was badly designed by a lets-get-everyone-involved international consortium. The shuttle can retrieve cargo from orbit -- a task that no one wants or needs. And it can ferry crew and cargo to orbit simultaneously, which is actually a terrible idea as it's cheaper -- and far safer -- to send crew and cargo up separately on smaller, task-specific craft. The Progress cargo ships and modern Soyuz capsules are examples of this principle.

Like most government projects, the shuttle looks good on camera and makes for great press, but is actually a terribly impractical and inefficient solution to a complicated set of problems.

And don't get me started on how bad the ISS is at every task it's been assigned.

Human spaceflight is 50 years old. We're past the "do it just to prove we can" stage. It's time to be grownups. It's time to build space technology that solves real problems in practical ways, rather than in ways that make contractors and photographers happy. We can achieve low earth orbit really easily and keep humans in that environment for months or years. We get it. We're good at it. Time to move on.

Now, if you want LEO cheaply, that's not what the government is good at. That's the job of the private sector. Government paves the way. The market makes it profitable. It's time for profitable LEO and human orbital habitation. NASA's job is to pave the way for the next level of hard stuff, and the next level is REALLY HARD.

Where is my advanced asteroid detection and deflection system? That's a serious problem that NASA should be solving and isn't.

Where is my proof-of-concept Helium-3 extractor for the moon, which would give us a legitimate reason for going there?

Where is my methane-oxygen autofactory for Mars, which is required before we even think about sending humans in that direction?

Where is my Lagrange-point automated telescope, which would make the Hubble look like a kid's toy magnifying glass and would actually require us to deal with serious, complex at-a-distance systems maintenance -- the kind of thing space colonies will represent?

Where is my FRAKKING SPACE ELEVATOR, which would actually be a serious surface-to-orbit gamechanger?

NASA has better things to do than keeping 30-year-old tech around for nostalgic PR purposes. I, for one, am glad to see them putting away childish things and -- hopefully -- getting down to serious business.

Consider, the shuttle is a reusable spacecraft that isn't actually reusable, given that the SRBs and main fuel tank are either lost or nearly 100% refitted after every launch. It's a construction platform for a spacestation that only needs a construction platform to assemble because it was badly designed by a lets-get-everyone-involved international consortium. The shuttle can retrieve cargo from orbit -- a task that no one wants or needs. And it can ferry crew and cargo to orbit simultaneously, which is actually a terrible idea as it's cheaper -- and far safer -- to send crew and cargo up separately on smaller, task-specific craft. The Progress cargo ships and modern Soyuz capsules are examples of this principle.

Like most government projects, the shuttle looks good on camera and makes for great press, but is actually a terribly impractical and inefficient solution to a complicated set of problems.

And don't get me started on how bad the ISS is at every task it's been assigned.

Human spaceflight is 50 years old. We're past the "do it just to prove we can" stage. It's time to be grownups. It's time to build space technology that solves real problems in practical ways, rather than in ways that make contractors and photographers happy. We can achieve low earth orbit really easily and keep humans in that environment for months or years. We get it. We're good at it. Time to move on.

Now, if you want LEO cheaply, that's not what the government is good at. That's the job of the private sector. Government paves the way. The market makes it profitable. It's time for profitable LEO and human orbital habitation. NASA's job is to pave the way for the next level of hard stuff, and the next level is REALLY HARD.

Where is my advanced asteroid detection and deflection system? That's a serious problem that NASA should be solving and isn't.

Where is my proof-of-concept Helium-3 extractor for the moon, which would give us a legitimate reason for going there?

Where is my methane-oxygen autofactory for Mars, which is required before we even think about sending humans in that direction?

Where is my Lagrange-point automated telescope, which would make the Hubble look like a kid's toy magnifying glass and would actually require us to deal with serious, complex at-a-distance systems maintenance -- the kind of thing space colonies will represent?

Where is my FRAKKING SPACE ELEVATOR, which would actually be a serious surface-to-orbit gamechanger?

NASA has better things to do than keeping 30-year-old tech around for nostalgic PR purposes. I, for one, am glad to see them putting away childish things and -- hopefully -- getting down to serious business.

Related articles

- Shuttle helped humans learn how to live in space (chron.com)

- Will This Spaceship Replace the Shuttle? (via SpaceJibe) (gcschileastronautics.wordpress.com)

- Obama to NASA: "New Technology 'Breakthroughs' Needed" (stevebeckow.com)

- Editorial: Shuttle's reach exceeded its grasp (knoxnews.com)

Friday, April 29, 2011

TechTalk Trivia: What 2 types of propulsion was Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft to use?

Image via WikipediaYet more damning evidence of my radio ineptitude courtesy of TechTalk on WRLR Chicago. This time around, I divulge what two types of spacecraft propulsion that Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft in history to use. If that sounds like your cup of tea, I promise the info survives my bludgeoning attempts at being entertaining.

Image via WikipediaYet more damning evidence of my radio ineptitude courtesy of TechTalk on WRLR Chicago. This time around, I divulge what two types of spacecraft propulsion that Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft in history to use. If that sounds like your cup of tea, I promise the info survives my bludgeoning attempts at being entertaining.More importantly, Mike Kastler explains how to use the Internet to up the efficiency and honesty of your charitable donations. Listen for that service, if nothing else. Skip over my trivia nonsense, if necessary.

Saturday, January 29, 2011

What symbolic item of cargo miraculously survived the Challenger disaster -- and is still in service today?

Image via WikipediaFive years ago, on the 20th anniversary of the Challenger disaster, I wrote this Geek Trivia column. Half a decade later, I modestly pass this bit of history on to my readers again.

Image via WikipediaFive years ago, on the 20th anniversary of the Challenger disaster, I wrote this Geek Trivia column. Half a decade later, I modestly pass this bit of history on to my readers again.What notable item of nonscientific cargo survived the Challenger disaster, going on to have its own unique, symbolic career?Read the complete column here.

An American flag on loan from Boy Scout Troop 514 from Monument, CO was onboard the Challenger when it broke apart, and salvage efforts recovered it from the Atlantic Ocean completely intact inside its sealed plastic container.

Now known as the Challenger Flag, it has enjoyed some storied exploits since its discovery during the Challenger wreckage recovery efforts. ... Though explosion all but destroyed the flag's commemorative case and a group of silver medallions along with the Challenger, the flag itself survived to fly at many notable events and locations. ...

NASA returned the flag to Troop 514 in late 1986, but it did not remain with them long. In early 1987, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Warren Burger designated the Challenger Flag as the official flag of the U.S. Constitution's Bicentennial celebrations. On Sept. 17, 1987, the Challenger Flag served as a featured part of the Constitutional Parade in Philadelphia, and the following day it flew once again above the U.S. Capitol.

The Challenger Flag then went into semi-retirement for the next 15 years, serving only as an honored artifact in Colorado Boy Scout Eagle Court ceremonies. Then, in 2002, the troop loaned the flag to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints for display in Salt Lake City while the city hosted the Winter Olympic Games.

Today, the Challenger Flag again resides in the possession of Troop 514, awaiting its next call to duty.

Related articles

- How the Challenger Disaster Changed My Life (xconomy.com)

- Remembering Challenger Disaster on its 25th Anniversary - International Business Times (news.google.com)

- Will human spaceflight ever be safe? (futurismic.com)

- NASA honors astronauts lost from Apollo, shuttles (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

Tuesday, November 09, 2010

Shuttle mission STS-2 featured the only all-rookie crew in space shuttle history -- except one of them was already an astronaut. Wait, what?

Image via WikipediaOn November 12, 1981, the space shuttle Columbia launched its second mission -- the first and last shuttle flight with an all-rookie crew. Neither Commander Joe Engle nor Pilot Richard Truly had ever flown in space before mission STS-2; NASA hadn't sent an all-space-novice team into orbit since Skylab 4 in 1973 and has never sent one since.

Image via WikipediaOn November 12, 1981, the space shuttle Columbia launched its second mission -- the first and last shuttle flight with an all-rookie crew. Neither Commander Joe Engle nor Pilot Richard Truly had ever flown in space before mission STS-2; NASA hadn't sent an all-space-novice team into orbit since Skylab 4 in 1973 and has never sent one since.Before you jump to conclusions, the performance of the STS-2 team is not the reason NASA informally banned subsequent all-rookie spacecraft lineups. While Engle and Truly did violate NASA orders during the mission, their performance was both laudable and daring. And if that seems counter-intuitive, wait until you realize that one of these two NASA rookies already earned his US astronaut wings before he ever entered the space program.

How did NASA send up an all-rookie crew on STS-2 if one of the crew members was already an astronaut?

Monday, November 01, 2010

Of the 75 artificial objects on the moon how many weren't put there by the US and USSR?

Image via WikipediaThree years ago this week, China's first lunar probe, Chang'e 1, entered orbit around the moon. Roughly 15 months later, Change'e 1 was intentionally crashed into the lunar surface (after recording the most complete and accurate 3D survey of the moon ever made), adding yet another item to the growing list of man-made objects on the moon.

Image via WikipediaThree years ago this week, China's first lunar probe, Chang'e 1, entered orbit around the moon. Roughly 15 months later, Change'e 1 was intentionally crashed into the lunar surface (after recording the most complete and accurate 3D survey of the moon ever made), adding yet another item to the growing list of man-made objects on the moon.Humanity has been chucking technology at the moon for over 50 years. The first human creation to contact the lunar surface was the Soviet Luna 2 probe in 1959. Since then, a total of 75 man-made objects have achieved lunar touchdown (or impact). Most of those items are of American or Soviet origin, products of the Cold War space race. Twenty years ago, Japan broke the Russo-American duopoly on lunar littering by crashing the orbiter portion of the Hiten probe on the moon. Since then, four more non-US and and non-Soviet/Russian space agencies have placed objects on the moon -- but the rest of the world has a long way to go before it overtakes the American-Russian rivalry in lunar tech-tossing.

Of the 75 artificial objects on the moon how many weren't put there by the US and USSR?

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

'The Revolution Will Be Distributed' ... +18 more must-read links

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia- The Revolution Will Be Distributed: Wikileaks, Anonymous And How Little The Old Guard Realizes What's Going On

- So When Does Apple Do Away With Hard Drives?

- Video: Spaceport America Inaugurated By Virgin Galactic’s VSS Enterprise

- A Sure Sign of the Apocalypse: Sears Zombies

- Implanted obsolescence

- X-Ray Scanner Vans Not Just Being Sold To Law Enforcement

- Oh Look, It Appears Music Video Games Were A Bit Of A Fad Too

- The meaning of a death in combat

- The Tea “Party” is more like a small gathering…of rich people.

- Star Trek cited by Texas Supreme Court

- 5 Reasons Lucas Should Film a New Star Wars Trilogy

- Sci-Fi's Cory Doctorow Separates Self-Publishing Fact From Fiction

- catrambo: E-publishing and Business Models

- Donate to a monkeypunk anthology, raise money for clean water

- Ben Kenobi, Private Eye

- Digg Faces Accusations Of Gaming Itself

- Audience as Currency

- Can Charity Work With A For-Profit Motive?

- Small Batch, Hand Crafted Outbound Marketing Works

Sunday, October 24, 2010

'Why's Foursquare NASA's Latest Frontier?' and 8 more must-read links

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia- Why's Foursquare NASA's Latest Frontier?

- Starbucks CIO shows why next version of Windows is "risky business" for Microsoft

- YouTube Trivial Pursuit is as addictive as the real thing

- Google finally admits Street View vehicles collected passwords, promises privacy fixes

- Focusing On Google Getting Emails & Passwords Via Data Collection Misses The Point: Anyone Could Have Done It

- There's Always A Way To Compete: Competing With Google By Being Human

- Twitter Employees Get Google’s 20% Time… For The Entire Next Week

- President Obama contributes to 'It Gets Better'

- Wonder Woman’s Earliest Costume Discovered

Saturday, October 23, 2010

'Wet moon would make a great launchpad' and 9 more must-read links

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia- Wet moon would make a great launchpad

- Creating stronger privacy controls inside Google

- Supreme Court Chief Justice Admits He Doesn't Read Online EULAs Or Other 'Fine Print'

- If Google TV Has To Pay To Make Hulu Available To Viewers, Will Mozilla Have To Pay To Access Hulu Via Firefox?

- The Future Of TV Is HTML

- Four-legged bomb detectors still top dog

- Movie Description FAIL

- Expand the Shelf Life of Free

- Why Direct Mail Can't Help Your Business Grow

- Backup For Cloud Apps

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

What was the original name of the Space Shuttle Enterprise?

Image via WikipediaA mere 34 years ago this week -- Sept. 17, 1976 -- the Space Shuttle Enterprise was revealed to the public with a Star Trek-themed press event. Gene Roddenberry and much of the original Star Trek series' principal cast were present, which was appropriate since it was a mass write-in campaign by Star Trek fans that prodded NASA into naming the original shuttle orbiter after the famous fictional starship.

Image via WikipediaA mere 34 years ago this week -- Sept. 17, 1976 -- the Space Shuttle Enterprise was revealed to the public with a Star Trek-themed press event. Gene Roddenberry and much of the original Star Trek series' principal cast were present, which was appropriate since it was a mass write-in campaign by Star Trek fans that prodded NASA into naming the original shuttle orbiter after the famous fictional starship.The space shuttle designated OV-101 was originally intended to bear a different name than Enterprise, one which has some intriguing parallels to Star Trek canon.

What was the original name of the Space Shuttle Enterprise?

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Besides our own moon, how many non-planets have humans successfully landed a spaceprobe on?

When it comes to space probes, there are three basic levels of design difficulty: Impactors, orbiters, and landers.

Impactors are literally designed to crash into other celestial objects, recording until they smash into another space rock, which saves flight engineers the trouble of targeting anything beyond a nearby gravity well.

Orbiters are designed to enter -- and in some cases slingshot through -- a nearby gravity well, which requires far more navigational calculus.

Landers, as you might imagine, require not only reaching another gravity well, but delicately succumbing it to it in such a fashion as to not crush or incinerate the space probe on its way to reaching the target surface.

When it comes to space probe targets, there are also three basic levels of difficulty: Our own moon, other local planets, and other local non-planets besides our own moon.

When it comes to space probe targets, there are also three basic levels of difficulty: Our own moon, other local planets, and other local non-planets besides our own moon.

The moon is biggest local gravity well besides the Earth itself. We've been crashing...er, impacting probes with the moon for fifty years, since the Soviet Luna 2 "flyby" in 1959. The moon is in Earth orbit, so hitting the moon is basic crashing one object in Earth gravity well into another.

Hitting another planet requires leaving Earth's gravity well and successfully falling into another one -- which isn't so easy with the sun out there trying to turn everything into another Sol-trapped pseudo-comet.

Hitting a non-planet besides the moon? That's the really hard trick, as you not only leave Earth's gravity well, but you have to hit a target usually trapped within the gravity well of another planetary body. That's bit like riding a waterfall and choosing which rock to land on at the bottom -- without ending up in the pool of water underneath.

It should comes as no surprise, then, that we've only in recent years been able to land a space probe on a non-planet besides our own moon, and we've only pulled it off a bare handful of times.

Besides our own moon, how many non-planets have humans successfully landed a space probe on?

It should comes as no surprise, then, that we've only in recent years been able to land a space probe on a non-planet besides our own moon, and we've only pulled it off a bare handful of times.

Besides our own moon, how many non-planets have humans successfully landed a space probe on?

Labels:

NASA,

Space,

truly trivial

Tuesday, March 02, 2010

Truly Trivial: Who does NASA's space sickness scale openly make fun of?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaMost historians don't bring up that last bit, but it may be Titov's most important historical contribution. Titov's zero-g upchuck was the first documented case of space adaptation syndrome, known colloquially as space sickness. NASA records show that roughly 60 percent of all astronauts suffer from space sickness on their first flight. Symptoms include dizziness, disorientation, and the aforementioned vomiting, which can collectively render a space traveler useless or, worse, a danger to his vessel and his crewmates.

NASA actually has an informal scale for measuring the severity of any specific case of space sickness, one which is named in "honor" of a particularly ignominious victim of space adaptation syndrome. And no, it's not Gherman Titov.

Who does NASA's space sickness scale openly make fun of?

Thursday, February 04, 2010

Nerd word of the week: Human-rated

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaI bring it up because: President Obama just pulled the plug on the the next NASA human-rated spacecraft, Project Constellation, in his recently proposed federal budget -- even as we edge closer to the retirement of the space shuttle program in September of this year with STS-133. (Whether this axing survives Congress remains to be seen, as the Bush-era Constellation program promised research dollars to several Congressional districts.) As it stands now, NASA is going to be out of the manned spaceflight business after this year, and may stay that way for years, even decades, and perhaps forever.

Scientists are torn over the Constellation shutdown: Upset that the promise of a manned presence on the moon, Mars, and even the asteroids has been nixed; relieved that an over-budget, backwards-looking retread of the Apollo program has been shut down in favor of more promising and practical telescope and robot-probe missions. Moreover, Obama is explicitly handing the human-rated baton over to private spaceflight, with the likes of SpaceX poised to pick up millions or even billions of dollars in NASA contracts if they find a commercial method of getting astronauts and cargo to and from the International Space Station. It could be a bold new era of affordable spaceflight, or just another decade or three of humanity trapped in the claustrophobic confines of Low Earth Orbit. Only time, and human-rated innovation, will tell.

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Truly Trivial: How many planets are known to have liquid surface water?

Last Friday, NASA announced that its LCROSS mission -- also known as "let's slam a probe into the lunar surface while another probe films the action, Jackass-style" -- found significant amounts of water on the moon. This revved up interest in lunar colonization again, despite the fact that there isn't any pure, drinkable, liquid water on the moon.

Now, water is very useful for space exploration even if you can't directly drink it, as simple electrolysis lets you crack water into breathable oxygen and hydrogen rocket fuel. The moon just became much more interesting as a weigh station for spacecraft, as robot factories could be sent ahead to stockpile hydrogen, oxygen, and possibly even purified drinkable water for manned craft heading further out into the solar system. Moreover, water is a very effective radiation shield, provided you can encircle a crew cabin in a two-meters-deep tank of H2O on all sides. The "significant amounts" of lunar water means moonbases might just be able to extract the Olympic swimming pools' worth of water necessary to ward off the cosmic fry-daddy rays awaiting space travelers.

As Karl Schroeder points out, the main barrier to manned spaceflight isn't technology but the expense of hauling the necessary materials into orbit. Launching these materials off the moon requires climbing out of one-sixth the gravity well that exists on Earth, which means there's an economic argument to be made for gathering spaceflight materials from a lunar base rather than launching them from Earth with the astronauts. Besides, if we can perfect the robot factories on the moon, we can get serious about mining comets, which have a lot more water-ice mass per capita and a lot less gravity. Robot comet iceminers mean that manned spacecraft could have a plethora of automated air, fuel, and shielding depots scattered throughout the Interplanetary Transport Network.

Thus, the lunar water discovery is very exciting, but it's unlikely to lead directly to the holy grail of space exploration -- the discovery of extraterrestrial life. Virtually all life as we know it requires water to exist, particularly liquid water that appears on the surface of the world, where it can be exposed to nurturing (and mutating) solar radiation. We've found hundreds of extrasolar planets and thousands of extraterrestrial non-stellar bodies, but liquid surface water remains stubbornly rare.

How many planets besides Earth are known to possess liquid surface water?

Now, water is very useful for space exploration even if you can't directly drink it, as simple electrolysis lets you crack water into breathable oxygen and hydrogen rocket fuel. The moon just became much more interesting as a weigh station for spacecraft, as robot factories could be sent ahead to stockpile hydrogen, oxygen, and possibly even purified drinkable water for manned craft heading further out into the solar system. Moreover, water is a very effective radiation shield, provided you can encircle a crew cabin in a two-meters-deep tank of H2O on all sides. The "significant amounts" of lunar water means moonbases might just be able to extract the Olympic swimming pools' worth of water necessary to ward off the cosmic fry-daddy rays awaiting space travelers.

As Karl Schroeder points out, the main barrier to manned spaceflight isn't technology but the expense of hauling the necessary materials into orbit. Launching these materials off the moon requires climbing out of one-sixth the gravity well that exists on Earth, which means there's an economic argument to be made for gathering spaceflight materials from a lunar base rather than launching them from Earth with the astronauts. Besides, if we can perfect the robot factories on the moon, we can get serious about mining comets, which have a lot more water-ice mass per capita and a lot less gravity. Robot comet iceminers mean that manned spacecraft could have a plethora of automated air, fuel, and shielding depots scattered throughout the Interplanetary Transport Network.

Thus, the lunar water discovery is very exciting, but it's unlikely to lead directly to the holy grail of space exploration -- the discovery of extraterrestrial life. Virtually all life as we know it requires water to exist, particularly liquid water that appears on the surface of the world, where it can be exposed to nurturing (and mutating) solar radiation. We've found hundreds of extrasolar planets and thousands of extraterrestrial non-stellar bodies, but liquid surface water remains stubbornly rare.

How many planets besides Earth are known to possess liquid surface water?

Thursday, November 05, 2009

Nerd Word of the Week: Spam in a can

Spam in a can (adj.) - Space program slang term for a passive occupant in a spacecraft, specifically a space capsule. The phrase is generally attributed to Chuck Yeagar, if only because he's shown describing the Mercury astronauts as "spam in a can" in the movie The Right Stuff, though there is ample evidence that multiple astronauts and NASA officials used the term liberally during the 1960s Space Race. The early Mercury astronauts, all trained military pilots, are known to have resisted being mere "spam in a can" with no active control of their vessels, thus forcing a level of human direction into early space vehicles.

Spam in a can is now typically used as a snarky criticism of the current level of manned spaceflight technology, as humans are still travelling as meat packed into primitive metal containers and shipped long distances. This falls under the sensawunda criticism of NASA -- particularly the space shuttle successor Project Constellation, which is described as "Apollo on steroids" -- in that we are still not creating or using the sci-fi-inspired tech that books and movies has promised us for decades. Warren Ellis and Colleen Doran rather deftly pointed out the spam-in-a-can disappointment factor with NASA in the graphic novel Orbiter, wherein an alien intelligence redesigns our "primitive" space shuttle into a true interplanetary exploration vehicle.

I bring it up because: Laika passed away 52 years ago on Tuesday. For those that don't know the name, Laika was the first living creature that humans sent into space. She was a Soviet space dog launched aboard Sputnik 2 on Nov. 3, 1957. She died from overheating a few hours after launch, thus making Laika the first spaceflight casualty. Her likeness is preserved in a statue at the cosmonaut training facility in Star City, Russia, as her nation's first space traveler. Telemetry from her mission proved that living beings could survive launch g-forces and weightlessness, thus proving that spam in a can was a viable manned spaceflight model.

I also mention the spam in a can principle as a corollary to Charles Stross's recent thought experiment blog post, How habitable is the Earth? Stross essentially argues that humans are explicitly designed for a particular fraction of Earth's environment that exists during a hyper-minute fraction of Earth's geological history, thus making human space exploration -- which removes us from this environment -- a terribly difficult and expensive undertaking. Karl Schroeder recently counter-argued (the point, not Stross) that most of these problems are surmountable if we get launch expenses down and can get the proper equipment -- all of which already exists -- into orbit cheaply. Which gets us back to the spam in a can criticism: Until the tech gets better, large-scale humans space exploration is a pipe dream.

Spam in a can is now typically used as a snarky criticism of the current level of manned spaceflight technology, as humans are still travelling as meat packed into primitive metal containers and shipped long distances. This falls under the sensawunda criticism of NASA -- particularly the space shuttle successor Project Constellation, which is described as "Apollo on steroids" -- in that we are still not creating or using the sci-fi-inspired tech that books and movies has promised us for decades. Warren Ellis and Colleen Doran rather deftly pointed out the spam-in-a-can disappointment factor with NASA in the graphic novel Orbiter, wherein an alien intelligence redesigns our "primitive" space shuttle into a true interplanetary exploration vehicle.

I bring it up because: Laika passed away 52 years ago on Tuesday. For those that don't know the name, Laika was the first living creature that humans sent into space. She was a Soviet space dog launched aboard Sputnik 2 on Nov. 3, 1957. She died from overheating a few hours after launch, thus making Laika the first spaceflight casualty. Her likeness is preserved in a statue at the cosmonaut training facility in Star City, Russia, as her nation's first space traveler. Telemetry from her mission proved that living beings could survive launch g-forces and weightlessness, thus proving that spam in a can was a viable manned spaceflight model.

I also mention the spam in a can principle as a corollary to Charles Stross's recent thought experiment blog post, How habitable is the Earth? Stross essentially argues that humans are explicitly designed for a particular fraction of Earth's environment that exists during a hyper-minute fraction of Earth's geological history, thus making human space exploration -- which removes us from this environment -- a terribly difficult and expensive undertaking. Karl Schroeder recently counter-argued (the point, not Stross) that most of these problems are surmountable if we get launch expenses down and can get the proper equipment -- all of which already exists -- into orbit cheaply. Which gets us back to the spam in a can criticism: Until the tech gets better, large-scale humans space exploration is a pipe dream.

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Truly Trivial: How did Wernher von Braun try to jumpstart a US space program a decade before NASA?

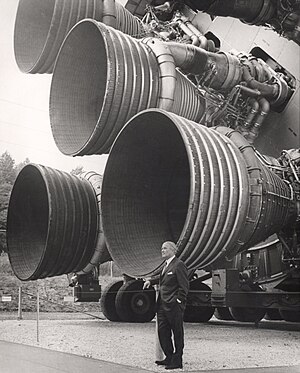

If one were to construct a Mt. Rushmore of rocket scientists, almost any quartet of visionaries enshrined there would have to include Wernher von Braun, architect of the early American manned spaceflight program. (For this geek's money, von Braun would be joined by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Robert Goddard, and Hermann Oberth, though you could also make a good case for Sergei Korolev as first alternate.) Fifty-one years ago tomorrow, President Eisenhower transferred von Braun and his team of engineers from the U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) -- where he built the famous Redstone rockets -- to the newly formed NASA, where von Braun would create the launch vehicles for the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs.

All of that, however, very nearly never came to be.

Wernher von Braun was the leader of a handful of German scientists that developed the infamous V-2 rockets that the Nazis used to bombard London during World War II. As Germany began to fall at the end of the war, various factions were vying to capture von Braun and his compatriots in order to secure the German rocket expertise for themselves. Moreover, von Braun rightfully suspected that the German SS had orders to execute the rocket scientists should it become likely that they would fall into enemy hands. Thus, von Braun and his team decided they should actively surrender to Allied forces before they could be killed; the only question was to which Allied nation?

Von Braun's group surrendered to the Americans, with von Braun's brother Magnus literally flagging down a U.S. infantryman riding a bicycle and shouting: "My brother invented the V-2. We want to surrender." Von Braun noted that they chose the Americans in part from fear of how they would be treated as POWs by the Soviets, who were also advancing on the position where the German rocketeers surrendered. Still, had von Braun's team been sequestered elsewhere (as nearly happened) or been forced to abandon their research and take up arms in defense of Germany (as other scientists were forced to do), he may never had made his way to NASA.

Once captured, the U.S. military had to "bleach" von Braun's record in order to clear him for service, as President Truman stipulated that no German war criminals could work for the United States. Wernher von Braun was an SS officer, and his V-2 rocket program employed slave labor, though von Braun himself claimed both actions were forced on him the Nazi power structure. After he was "cleared" to design rockets for the U.S., the military assigned him to build missiles, rather than space vehicles -- despite the fact the von Braun actively campaigned for a manned spaceflight program.

Thus, von Braun resorted to a rather unusual public relations maneuver in an attempt to "jumpstart" public demand for manned spaceflight in 1949 -- nine years before NASA existed.

How did Wernher von Braun try to jumpstart a US space program a decade before NASA?

All of that, however, very nearly never came to be.

Wernher von Braun was the leader of a handful of German scientists that developed the infamous V-2 rockets that the Nazis used to bombard London during World War II. As Germany began to fall at the end of the war, various factions were vying to capture von Braun and his compatriots in order to secure the German rocket expertise for themselves. Moreover, von Braun rightfully suspected that the German SS had orders to execute the rocket scientists should it become likely that they would fall into enemy hands. Thus, von Braun and his team decided they should actively surrender to Allied forces before they could be killed; the only question was to which Allied nation?

Von Braun's group surrendered to the Americans, with von Braun's brother Magnus literally flagging down a U.S. infantryman riding a bicycle and shouting: "My brother invented the V-2. We want to surrender." Von Braun noted that they chose the Americans in part from fear of how they would be treated as POWs by the Soviets, who were also advancing on the position where the German rocketeers surrendered. Still, had von Braun's team been sequestered elsewhere (as nearly happened) or been forced to abandon their research and take up arms in defense of Germany (as other scientists were forced to do), he may never had made his way to NASA.

Once captured, the U.S. military had to "bleach" von Braun's record in order to clear him for service, as President Truman stipulated that no German war criminals could work for the United States. Wernher von Braun was an SS officer, and his V-2 rocket program employed slave labor, though von Braun himself claimed both actions were forced on him the Nazi power structure. After he was "cleared" to design rockets for the U.S., the military assigned him to build missiles, rather than space vehicles -- despite the fact the von Braun actively campaigned for a manned spaceflight program.

Thus, von Braun resorted to a rather unusual public relations maneuver in an attempt to "jumpstart" public demand for manned spaceflight in 1949 -- nine years before NASA existed.

How did Wernher von Braun try to jumpstart a US space program a decade before NASA?

Thursday, October 01, 2009

Nerd Word of the Week: Sensawunda

Sensawunda (n.) - Sci-fi slang term for sense of wonder, used to describe emotionally stirring or intellectually stimulating concepts depicted within speculative fiction. Golden Age science fiction is often lauded for its surplus sensawunda, with point-of-view characters constantly amazed at the scope, scale, and strangeness of creatures, locales, and technologies featured in these sci-fi stories. A.E. Van Vogt's Empire of Isher series is often cited as a classic example of a sensawunda tale, as are the various Heinlein juveniles like Rocket Ship Galileo and Farmer in the Sky. To this day, the original Star Wars is held up as the paramount cinematic example of sensawunda, even if its various prequels utterly failed to live up to this standard.

Contemporary science fiction is often criticized for lacking sensawunda, especially as concerns fashionably cynical or jaded protagonists who are never amazed or inspired by their objectively fantastic and extraordinary experiences. Many critics have cited this sensawunda deficit as the reason why fantasy has overtaken science fiction in mainstream literary success, with the Harry Potter phenomenon -- and its willing embrace of sensawunda -- serving as exhibit A. Moreover, many modern characters are meta-aware, often acting as if they know they are in a fictional setting and using their knowledge of standard spec-fic tropes to navigate and outsmart the challenges of their own stories. This has the effect of being alternately hilarious (in the case of Terry Pratchett's Discworld series) or diminishing of the story; if the main character does not take it seriously, how can the reader? Iain Banks and John Varley have consciously tried to recapture the sensawunda flair of these classic sci-fi tales, with Varley explicitly channeling Heinlein juveniles in his Red Thunder and its sequels, and Banks engaging in gleeful Golden Age romanticism in his novel Feersum Endjinn.

I bring it up because: Today is the 51st anniversary of the incorporation of NASA, and if ever a real-world entity attained and then lost a sensawunda, it's the American space agency. While NASA is objectively doing faster, better, cheaper space exploration today with its advanced satellites, deep-space probes and robot rovers, it has lost the pioneer flare (and bottomless Cold War budget) that captured the imagination during the heady days of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. The upcoming Project Constellation and its Ares V rockets and Altair and Orion spacecraft harken back to the golden age of manned spaceflight, but no one is certain they will ever actually get built and, if they do, whether they'll feel just like a remake of a classic tale that has, sadly, loss it originality and sensawunda. Let's hope the critics are wrong, because the world is a brighter place when our reach exceeds our grasp, and the sky is filled with manned rockets daring for the stars.

Contemporary science fiction is often criticized for lacking sensawunda, especially as concerns fashionably cynical or jaded protagonists who are never amazed or inspired by their objectively fantastic and extraordinary experiences. Many critics have cited this sensawunda deficit as the reason why fantasy has overtaken science fiction in mainstream literary success, with the Harry Potter phenomenon -- and its willing embrace of sensawunda -- serving as exhibit A. Moreover, many modern characters are meta-aware, often acting as if they know they are in a fictional setting and using their knowledge of standard spec-fic tropes to navigate and outsmart the challenges of their own stories. This has the effect of being alternately hilarious (in the case of Terry Pratchett's Discworld series) or diminishing of the story; if the main character does not take it seriously, how can the reader? Iain Banks and John Varley have consciously tried to recapture the sensawunda flair of these classic sci-fi tales, with Varley explicitly channeling Heinlein juveniles in his Red Thunder and its sequels, and Banks engaging in gleeful Golden Age romanticism in his novel Feersum Endjinn.

I bring it up because: Today is the 51st anniversary of the incorporation of NASA, and if ever a real-world entity attained and then lost a sensawunda, it's the American space agency. While NASA is objectively doing faster, better, cheaper space exploration today with its advanced satellites, deep-space probes and robot rovers, it has lost the pioneer flare (and bottomless Cold War budget) that captured the imagination during the heady days of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. The upcoming Project Constellation and its Ares V rockets and Altair and Orion spacecraft harken back to the golden age of manned spaceflight, but no one is certain they will ever actually get built and, if they do, whether they'll feel just like a remake of a classic tale that has, sadly, loss it originality and sensawunda. Let's hope the critics are wrong, because the world is a brighter place when our reach exceeds our grasp, and the sky is filled with manned rockets daring for the stars.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=2d87219c-36e5-4c73-a8dc-cca2f2864b3c)